An electoral system is a set of rules governing elections, determining how votes are counted in order to determine which candidate(s) wins the election. There are lots of ways electoral systems can vary, including how many votes are needed to win the election, whether you vote for a single candidate, party’s list of candidates, or you rank several candidates, and whether the district elects one representative or several, among others. Together, different combinations form different electoral systems.

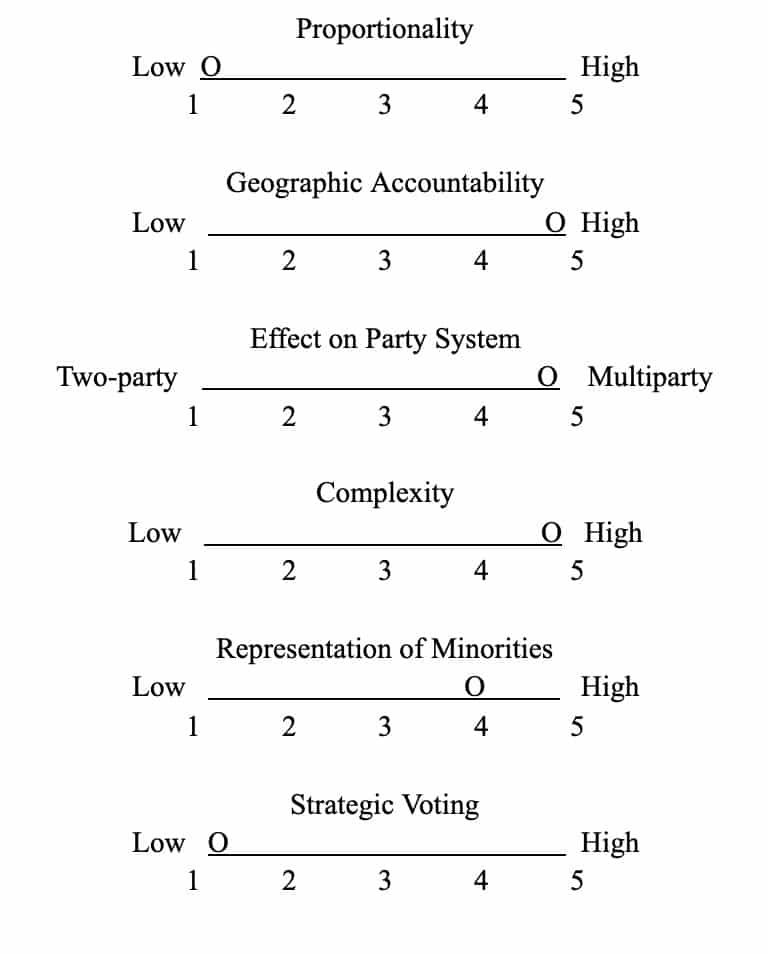

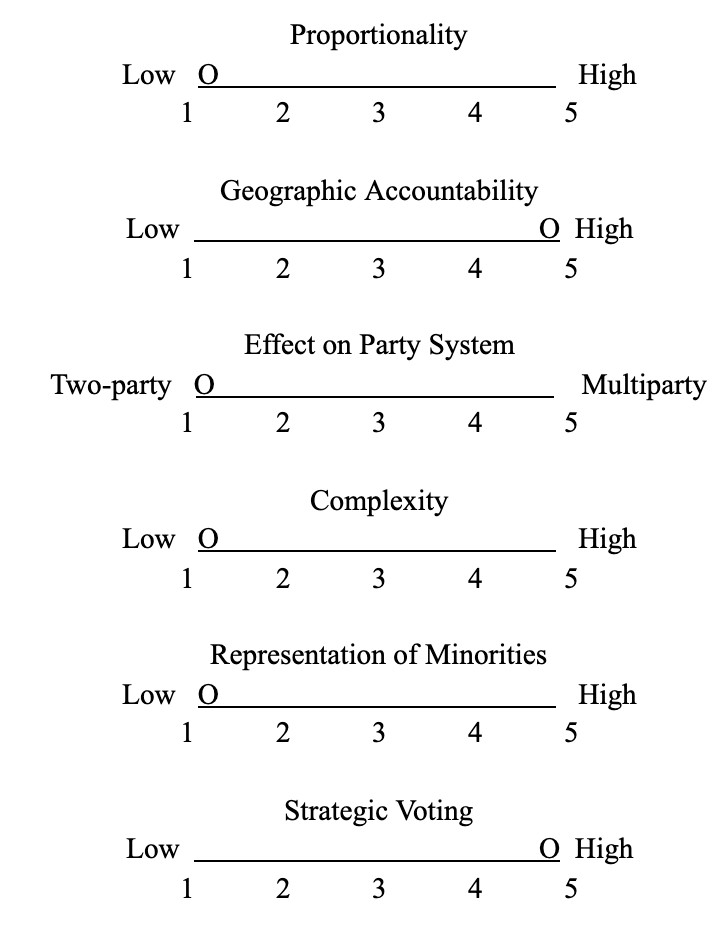

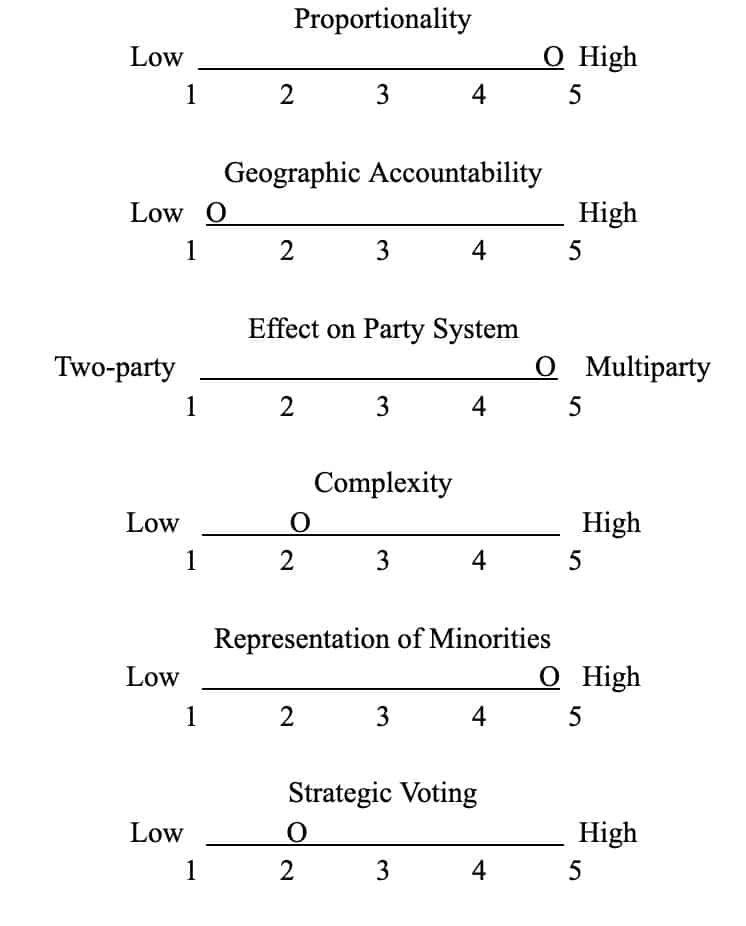

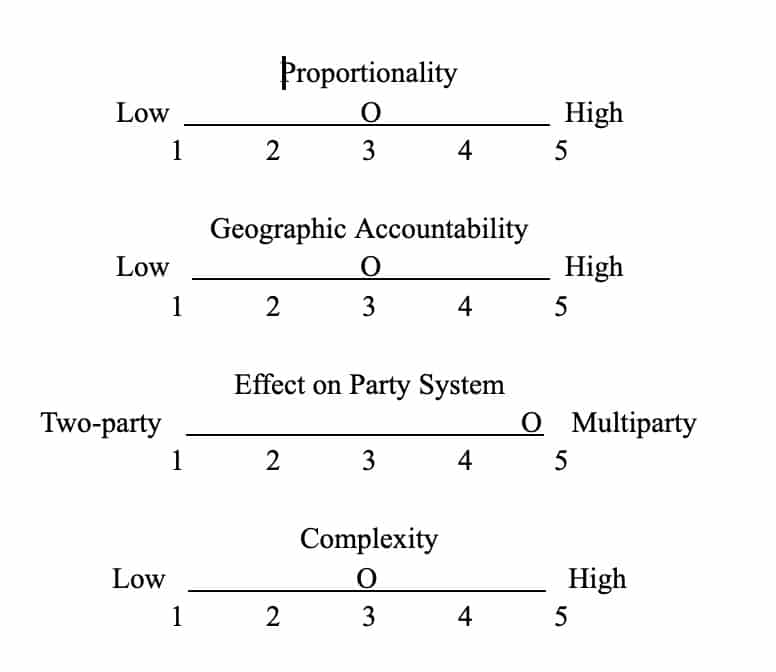

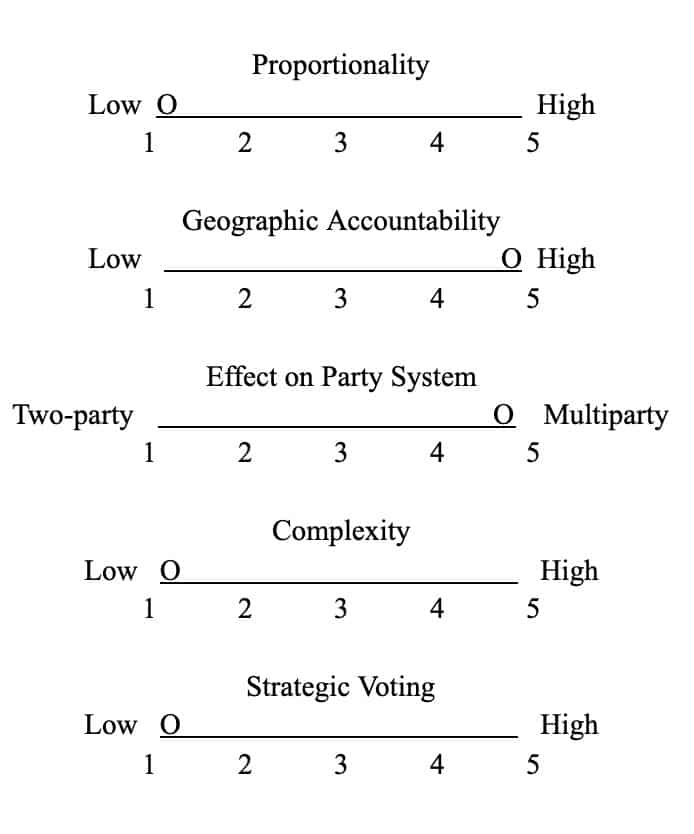

There are also separate criteria that can be used to evaluate each system as a whole. Each criterion is best understood as a spectrum, but there is not necessarily a correct or incorrect end of the spectrum, rather all of these criteria can be good or bad depending on the context.

- Proportionality: how closely the system translates votes won into seats won. This is most often related to what percentage of the votes is needed to win a seat. Wasted votes are votes that do not help elect a candidate.

- Geographic accountability: how accountable a specific elected representative is to voters of a defined geographic region. This can shape how easy it is for voters to influence policy, get help with local services and issues, and remove an unsatisfactory politician from office. In general, the more representatives per district, and the larger the district, the weaker the connection.

- Party system: the number and size of major political parties in the nation’s legislature, and different electoral systems can create stronger/weaker party systems from the same public opinion. The most common party systems are two-party and multiparty systems, both frequently found in democratic nations, and single-party systems more common in authoritarian or weak democratic states.

- Complexity: how much effort, knowledge, and education does it take for a voter to be informed? How many candidates or parties must a voter form an opinion on to make an informed vote?

- Representation of minorities: does the system encourage parties to run minority candidates or a diverse list of candidates, or does it encourage parties to run a candidate who must appeal to the majority of the district, who is likely not a minority member?

- Tactical/strategic voting: when a voter supports a candidate or party other than their most preferred candidate in order to prevent their least preferred candidate from getting elected.

The electoral system utilized in a country is often a product of its history. Many former colonial nations use electoral systems adapted from their colonizers, for instance many former British colonies use the First Past the Post system used in the UK. Additionally, once an electoral system is in place, it can be very difficult to change.

Electoral Systems

First Past the Post (FPTP)

In First Past the Post, electoral districts are relatively small and each only elects one representative (called a single-member district). To win a seat, a candidate needs more votes than any other candidate in the election (a plurality), which is not necessarily a majority of votes. It is possible for a party to win most or all of the seats with a much lower percentage of the vote. FPTP systems tend to develop two-party systems, because there is no benefit for coming in second (or later places), only parties that can reliably win elections survive, cutting out third parties. Voters also see the lack of success of third parties, and turn away from them, exacerbating their problems.

Canada uses the FPTP system, and the most recent federal election was in 2019. The Canadian House of Commons has 338 districts called “ridings”. Because many ridings had several of Canada’s larger political parties contesting the election, in some ridings the winner did not get a majority of the vote. At an extreme, in one riding the winner only earned 28.5% of the vote. Some parties’ representation in the House of Commons were more proportional than others; for instance the Conservative Party won 34.4% of the national vote and 121 ridings, which is nearly the same percentage of the House of Commons. While the New Democratic Party won 15.9% of the national vote this only equated to 24 ridings, or 7% of the House of Commons.

Proportional Representation (PR)

In List PR, electoral districts are typically larger, but elect more representatives than any one district does in FPTP. Parties run a list of candidates in each district, and voters vote for a party list rather than individual candidates. Parties win the number of seats proportional to the percentage of votes they earned. If a party wins X seats in a district, the top X candidates on their party list are elected. Because a party does not need a plurality of votes to enter the legislature, there will often be many, smaller parties in the legislature, forming a multi-party system. However, there can be a minimum percentage of the vote needed to earn a seat.

The European Parliament is one of the governing bodies of the European Union and is directly elected by the citizens of EU member states. Each member state elects Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) and the number of MEPs is dependent on population, currently ranging from 6-96 MEPs. Most states use the list PR system described above, though another system, single transferable vote, is also allowed.

Parallel Voting

Parallel Voting is one way to combine plurality/majority systems and PR. Voters cast two votes, one in a plurality/majority election (most typically FPTP but others are possible), and one vote in a PR election. How many seats a party wins in the plurality/majority election does not affect the number of seats that party wins in the PR election, or vice versa.

One nation that uses Parallel Voting is Italy. Italy’s Chamber of Deputies (lower house) has 630 seats, 233 (37%) of which are elected by FPTP, while the other 397 seats are elected by PR elections in regional, multi-member districts.

Two Round System (TRS)

Under TRS, each district elects one representative, and an absolute majority of votes is required to win, rather than a plurality as under FPTP. If no candidate initially wins more than 50% of the vote, another round of elections is held, traditionally between the top two candidates. This runoff is usually held a few weeks after the first round of elections.

France uses TRS for both its presidential and parliamentary elections. In the French 2017 presidential election, five candidates received more than 5% of the vote in the first round, with Emmanuel Macron (24.01% of the vote) and Marine Le Pen (21.3%) leading the pack. In the runoff between the two, Macron won with 66.1% of the vote, compared to Le Pen’s 33.9%.

Preferential Voting

Preferential voting is also known as alternative voting or ranked choice voting in the US. Like FPTP, preferential voting elects one representative per district, but unlike FPTP, voters indicate their preferences by ranking the candidates. Voters have a first preference vote, second preference vote, etc. Some nations require voters to rank all candidates, while others do not. To determine the winner, all first preference votes are counted. If a candidate has a majority of votes, that candidate is elected. If no candidate has a majority, then the candidate with the fewest votes is excluded, and that candidate’s votes are distributed according to the voters’ second preferences. This continues until a candidate has a majority (more than 50%) of the votes and they are declared the winner. This process is also known as an instant runoff, as opposed to the more time-consuming second round of elections in TRS.

Australia uses preferential voting, and it has gained traction in the US in recent years (under the name of ranked choice voting.) In Australia’s 2019 federal election, 46 seats were decided on the first preference vote, while the other 105 seats were decided on later preference votes. In twelve elections, the eventual winner was not in first place after the first round of preference votes, and ten of those elections went to the Labor party.