The Central American Minors Program (CAM) provides Guatemalan, Salvadoran, and Honduran children the opportunity to reunite with their parents living in the U.S. through refugee resettlement or parole. The Obama administration created CAM in 2014 and the Trump administration shut down the program in 2018. However, in March 2021, Biden announced he was restarting CAM in two phases. Beginning in March 2021, resettlement agencies started reopening cases that were closed in 2018, and in September 2021, they began accepting new applications.

Rising Numbers of Unaccompanied Minors

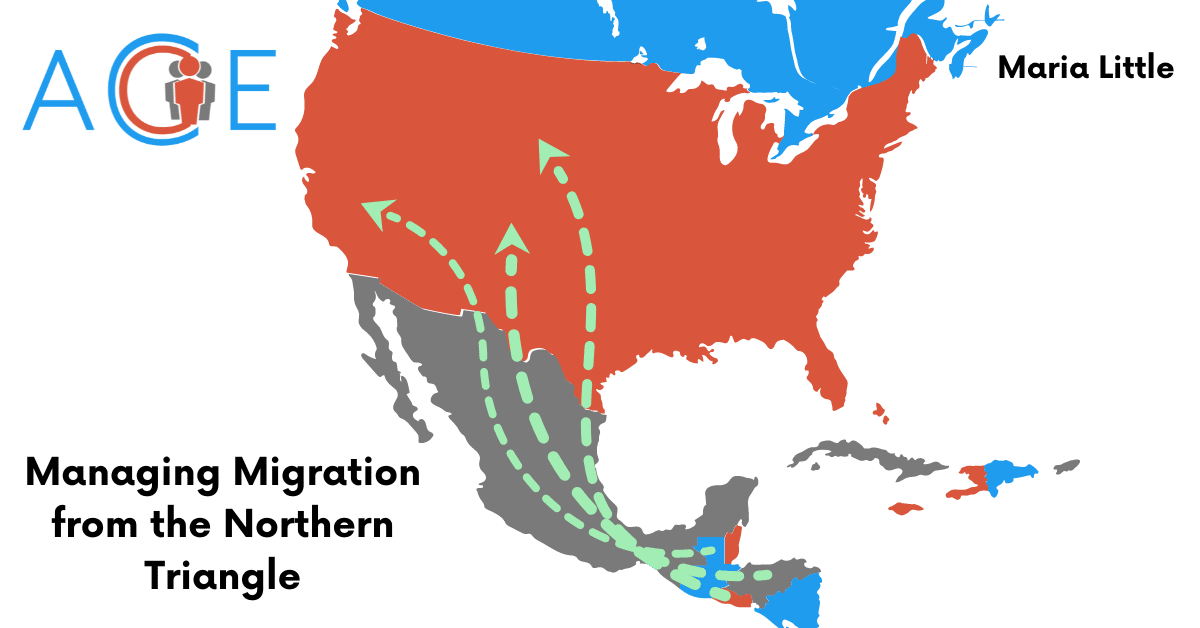

Both versions of CAM were a response to growing numbers of unaccompanied Central American minors arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border and the high-risk nature of child migration. Since 2012, 77% of apprehended unaccompanied minors are from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Researchers attribute this to violence and organized crime in Northern Triangle countries which have targeted youth in recent years. Another motivator for unaccompanied minor migration is reunification with parents in the U.S. and U.S. immigration policy that favors Central American children once they arrive. However, the journey to the U.S. is dangerous, as minors are more vulnerable to criminal organizations and human trafficking during travel.

UAC Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, by Country of Origin, FY2008-FY2021, CRS

In 2014, the number of unaccompanied minor encounters reached what was then a record high of 68,541 apprehensions. In response, Obama started CAM to discourage irregular and unsafe migration of children. The program reviewed 6,300 applications, approved 99% of them, and transported about 4,600 children and qualifying relatives to the U.S. However, when the Trump administration shut down CAM in 2018, 2,714 approved children did not immigrate.

The pandemic worsened economic conditions in Northern Triangle countries and exacerbated violence against at-risk children, many of whom were forced to quarantine with their abusers. In 2021, there was a new peak in unaccompanied minor encounters with 112,192 apprehensions in the first 10 months, prompting the Biden administration to relaunch CAM.

How does it work?

First, parents who want to bring their children living in Guatemala, El Salvador, or Honduras to the U.S. fill out an application through a refugee resettlement agency. Under the Obama administration, only parents who were Lawful Permanent Residents, Temporary Protected Status, Parole, Deferred Action, Deferred Enforced Departure, or Withholding of Removal could apply. Biden extended eligibility to legal guardians in all these categories, and parents or guardians with pending asylum applications or pending US visa petitions filed before May 15, 2021. Next, humanitarian offices in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras make contact with the child. Minors may be stepchildren or adopted, but must be under the age of 21 and unmarried. Once contact has been made, the child goes through multiple rounds of questioning at a humanitarian office, and agencies determine if the child is eligible for refugee status or parole. If approved, parents must pay for and submit a DNA test, and guardians must prove their guardianship with an affidavit. Their children are then flown to the U.S.

Recent developments

Biden’s eligibility requirements, which some expect will expand the program by 100,000 petitioners, have been the most significant change to CAM. However, in January 2022, the attorneys general in Texas, Arkansas, Alaska, Florida, Indiana, Missouri, Montana, and Oklahoma filed a lawsuit against CAM. They state that the program is illegal because it rewards undocumented immigrants, and Biden does not have the authority to enact it without the approval of Congress.

Arguments in Support of CAM

Proponents describe CAM as an effective pathway to legally reunite Central American children with their parents. To supporters, it represents a humanitarian exercise offering a new model for refugee adjudication, because it prioritizes the safety of minors. For example, minors that are not eligible for refugee status can still be paroled in the U.S. if they are found in danger. That being said, some argue that children will travel unaccompanied to the border whether or not they are accepted to CAM because there is a greater guarantee they will be admitted into the U.S. once they arrive.

Supporters also assert that CAM will decrease unaccompanied minor arrivals at the border. The program aimed to be the primary immigration channel for Central American minors, reducing border crossing. After its implementation in 2014 unaccompanied minor encounters decreased by 45%, although this did not last. Therefore, opponents say that CAM instead incentivizes the irregular migration of parents who will be able to bring their children later.

Arguments against CAM

A major criticism of CAM is that its current structure does not help or reach enough children in need. Of the 3,131 cases closed in March 2018, only 1,472 were reopened by February 2022, and the program’s first year saw an 82% decrease in the number of applicants given refugee status. Critics contend that the program only reaches a fraction of Central American children seeking reunification with their parents. Notably, 86% of qualifying children under Obama were Salvadoran, leaving out many children in Guatemala and Honduras. Additionally, the long application process and financial barriers complicate the process for parents in the U.S., while limited language access, dangerous journeys to interview locations, and safety risks while awaiting CAM determinations make it difficult for children in their home countries. On the other hand, supporters praise the program for the speed under which it was originally designed and its innovative approach to immigration policy.

Critics also argue that CAM burdens resettlement agencies and U.S. resources. Expanded eligibility and local office closures under Trump have overwhelmed refugee resettlement agencies with old and new cases only they can file. Furthermore, the resettlement of CAM recipients places added pressure on U.S. social services, like schools and healthcare programs, where children are settled.

Lastly, opponents claim that CAM increases irregular migration and takes away resources from other Latin American refugees. The eligible immigration status categories are usually given to undocumented migrants, so some say that the program disincentivizes migrants from using lawful immigration pathways like sponsoring their children through green cards. They also contend that these children do not meet refugee status and take away spots from the refugee cap, thereby decreasing the amount of other Latin American refugees allowed to immigrate. However, supporters maintain that the CAM is an essential lifeline for Central American children at risk of persecution and violence, regardless of their ability to meet refugee status.