History

In the wake of World War II, delegates from fifty nations met in San Francisco and unanimously adopted the final version of the Charter of the United Nations. The Charter set forth a mandate to maintain international peace and security. The mission to promote international cooperation was a familiar yet challenging goal. The League of Nations, established after World War I, embraced a similar initiative. However, the organization was ultimately unsuccessful in preventing the Second World War. President Harry Truman advocated for the Charter’s ratification and emphasized its importance in his address to the United States Senate:

“In your deliberations, I hope you will consider not only the words of the Charter but also the spirit which gives it meaning and life… It is the product of many hands and many influences. It comes from the reality of experience in a world where one generation has failed twice to keep the peace. The lessons of that experience have been written into this document.”

President Harry S. Truman, July 2 1945

Unlike its predecessor, the UN Charter was drafted during wartime and granted smaller nations a voice in its inception. The League of Nations halted operations following the creation of the UN and granted the new organization access to all of its archives and resources.

Structure

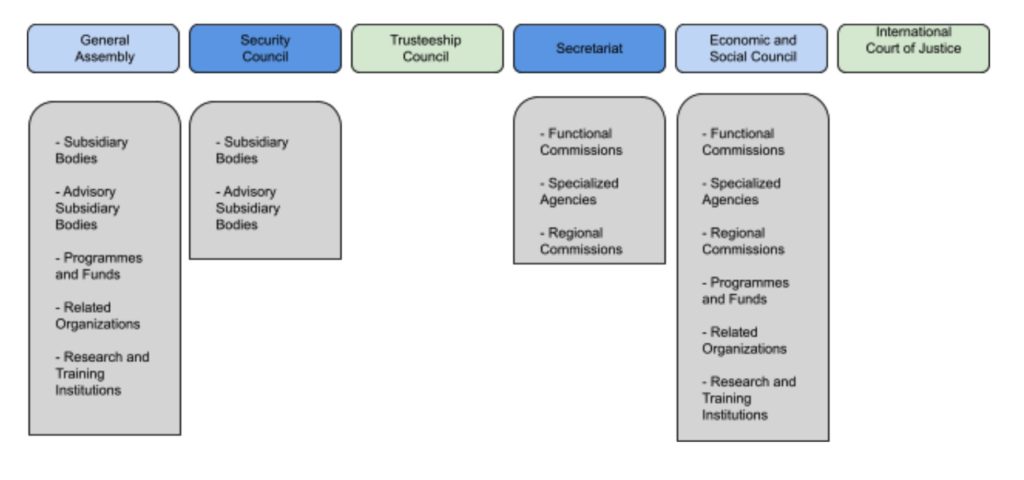

The Charter of the United Nations established the following principal organs:

- General Assembly: The GA is the main deliberative body of the UN. Each of the UN’s 193 member states are granted a vote in all GA matters.

- Security Council: The UNSC is tasked with the actual maintenance of international peace and security. The UNSC has the unique power to deploy peacekeepers, enact sanctions, and authorize military action. The council is made up of fifteen members, five of which are permanent (P-5) members who enjoy veto power. The P-5 members are China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The other ten members serve two-year terms.

- Economic and Social Council: ECOSOC is under the jurisdiction of the General Assembly and focuses primarily on economic and social issues. The GA elects the council’s 54 members to serve three-year terms.

- International Court of Justice: The ICJ is the judicial body of the UN. It settles disputes between states concerning violations of international law and acts as an advisory body to other UN bodies and agencies.

- Secretariat: The Secretariat is the executive body of the UN. The Secretary General has the power to set the agenda within the UNSC and oversee the daily operations of the UN.

Agencies and Funds

The image above illustrates the integrated nature of the UN system. Specialized agencies, funds, and commissions work alongside the main organs to supplement resolutions with expert research and a means to carry out the initiatives passed by the UN. Specialized agencies, unlike funds and programs, are independent international organizations who partner with the UN. For example, the International Monetary Fund works alongside the General Assembly to support initiatives concerning economic development.

Principles

According to the Charter, the UN holds itself to the following principles:

- Sovereign equality

- Peaceful conflict resolution

- Refusal to threaten force against any independent state

- Refrainment from providing assistance to a state against which the United Nations is taking preventive or enforcement action

- Refusal to intervene in matters which are within the domestic jurisdiction of any state unless the matter is brought to the UN for settlement

- Universal application of these principles for non-member states

Operations

The UN aims to improve quality of life across the globe in order to prevent conflict and maintain international peace and security. The organization works on a range of issues including, but not limited, to sustainable development, gender equality, disarmament, non-proliferation, disaster relief, refugee protection, drug trafficking, global trade, and infectious disease prevention. There are also thirteen ongoing peacekeeping operations, most notably in the Golan Heights, India, Pakistan, and South Sudan.

For example, the UN General Assembly works alongside the United Nations Development Program and the World Food Program to provide Syrian refugees with food, healthcare, temporary housing, and access to educational programs. Following an 8.8 magnitude earthquake in Chile in 2010, the UN worked alongside the World Health Organization to deliver medical care and supplies to the nearly 2 million Chilean citizens affected. More recently, the UN created the COVID-19 Response and Recovery Trust Fund to assist less developed countries in crafting a sustainable response to COVID-19 and catalyze economic recovery.