AUKUS Partnership Outline

The AUKUS Partnership was one of the first major foreign policy actions of President Biden’s Administration. On September 15, 2021, AUKUS partners released a joint statement announcing the agreement. The goal of the partnership is to promote information and technology sharing, and integrate security and defense measures by increasing cooperation on a variety of capabilities, with a focus on the Indo-Pacific Region.

The AUKUS Partnership has three pillars

- Provide Australia with “conventionally armed, nuclear powered submarine capabilities (SSN)”. Prior to this agreement, this technology was limited to six nuclear capable states (U.S.,UK, France, Russia, China, and India). The U.S. previously shared SSN technology with the UK, and AUKUS now extends this to Australia, a non-nuclear state. As such, this partnership is set to revolutionize Australian naval capabilities, which have struggled to travel longer distances due to limitations of electrically powered submarine fleets.

- Advance military capabilities “to promote security and stability in the Indo-Pacific Region”. The AUKUS partnership outlines objectives to expand and develop technologies, such as: AUKUS Undersea Robotics Autonomous Systems (AURAS, the development of robotic undersea technologies), AUKUS Quantum Arrangement (AQuA, development of quantum technologies), cooperation on Artificial Intelligence (AI), collaboration on hypersonic and counter-hypersonic capabilities, and the development of cyber capabilities and security measures.

- Commit to information exchange. As of February 8, 2022, The Exchange of Naval Nuclear Propulsion Information Agreement (ENNPIA) came into effect, resulting in AUKUS partners sharing nuclear propulsion intel trilaterally, the first agreement to do so with a non-nuclear capable state.

U.S. Favorability of UK Partnership

Prior to the introduction of the AUKUS Partnership, the UK had limited influence or presence within the Indo-Pacific Region, with the only formal international agreement being their membership in the Five Eyes security alliance. However, this new partnership indicates a significant shift in UK foreign policy , confirming the UK’s intention to align with U.S. foreign policy in the Indo-Pacific.

Figure showing the Overlap of Defense, Intelligence, and Security Groups in the Indo-Pacific Region.

The AUKUS Partnership presented significant political fallout in U.S.–Europe relations, because it prioritized the UK security partnership over a broader European security pact.

France was the most affected by the establishment of the AUKUS partnership as Australia withdrew from a previously agreed Franco-Australian Submarine deal to join AUKUS. This led to an increased strain on the U.S.–France Relations, due to both the loss of a multi-billion Euro agreement and the creation of a new security alliance formed without major European allies. Following the announcement of the AUKUS partnership, the new alliance took significant attention away from the European Union’s (EU) own policy plans for the Indo-Pacific Region. Given the contentious relations between the UK and the EU in a post-Brexit Europe, this partnership highlighted a perceived favoritism of U.S.–UK relations as loyal security partners, over a united Europe. In addition, with the introduction of the AUKUS Partnership, the agreement has strengthened an EU-independent UK as the only European state with significant security partnerships within the Indo-Pacific region.

Ramifications of the AUKUS Partnership

The response to the AUKUS partnership has been mixed. As discussed, the pact strained U.S.-French relations, and distanced the U.S. from Europe in terms of Indo-Pacific cooperation. Some believe this may lead to the EU pursuing its own independent security strategy when dealing with contentious U.S. and China relations, a position that has been publicly supported by French President Emmanuel Macron.

The AUKUS partnership, however, will have the most on-the-ground impact within the Indo-Pacific region. Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) reactions have been divided on the new security partnership present in the region. Recent analysis shows that 36.4% of ASEAN respondents say AUKUS would help “balance China’s growing military power”, yet 22.5% say the deal could spark “a regional arms race”. Overall there is a worry of what the broader consequences of agreements such as AUKUS may be, and their effects on the stability of the region.

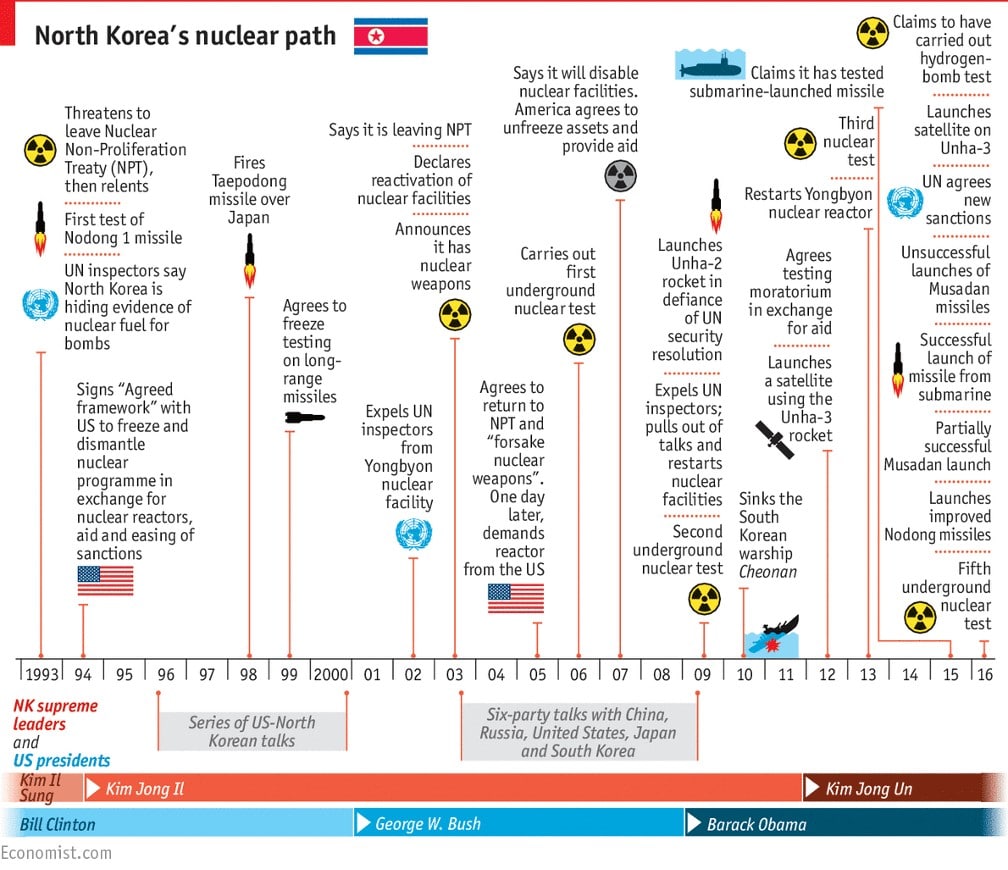

A major concern of the AUKUS Partnership is the potentially dangerous precedent an agreement of this nature could set for nuclear proliferation. While all three partners emphasized their commitment against nuclear proliferation, this agreement is the first to allow a non-nuclear capable state to access nuclear technology. In addition, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) requires non-nuclear states to declare all nuclear material, with the IAEA verifying the material is not being used for weaponry development, thus acting as a deterrence for nuclear proliferation. However, the NPT relies on states to self-monitor naval nuclear reactors because of practical issues with access. Australia is setting a precedent as the first non-nuclear weapons state with nuclear materials the IAEA is not monitoring. It could be dangerous if other countries follow this path, and derail the current global nuclear nonproliferation system. While Australia may not prove to be an exploitive threat to nuclear weapons development through the AUKUS partnership, a future agreement of this nature could serve as the perfect cover for potential would-be-proliferators to advance nuclear development programs under the guise of access to nuclear material through naval reactors, no longer checked by the IAEA.

US–UK Relations and Nuclear Proliferation

A 2020 report by Pew Research demonstrates that nuclear nonproliferation is a major foreign policy issue in the United States; 73% of Americans perceive the “spread of nuclear weapons” as a major threat to the U.S. This position attracts bipartisan support, with both Democrats and Republicans responding in equal measure to the perceived international threat. Moreover, 80% of respondents favor state cooperation with other countries as “very important” when navigating the spread of nuclear weapons.

The United States (U.S.) and the United Kingdom (UK) have a long history of alignment on foreign policy objectives towards nuclear proliferation and the threat of nuclear war. Much of the existing U.S.–UK agreements on nuclear cooperation between both states derive and build upon the original 1958 “Atomic Energy. Cooperation for Mutual Defense Purposes” agreement, which bound both countries in a united front against other state development of atomic weapons. As such, the Australia–United Kingdom–United States (AUKUS) Partnership is yet another foreign policy step the U.S. and the UK have taken to further their allied cooperation to address the international security threats of today.